Music and Poetry

Manos Tasakos is an important author and poetry critic, but also one of those who strive for the good of this land, working tirelessly and without self-interest. I know that one of his main life goals is the creation of a museum of modern Greek literature. Truly, what a wonderful idea for our culture! He is the one who formulated and proposed this plan, and is zealously working for the fulfillment of this great purpose. We hope he succeeds.

On the occasion of Radio Art’s fresh start, I asked him to share a few reflections on music, poetry, the arts, and language.

We sincerely thank him. His text can be found below.

Music, poetry, arts, language; reflections

Manos Tasakos

Voices

Ideal, beloved voices

of those who’ve died, or those

who are like dead to us…

They speak to us in dream sometimes;

sometimes, in thought, the mind can hear them.

And with their sound we hear returning

the sounds of our life’s oldest poetry -

like music, distant in the night, that’s fading…

Kavafis, of course. And the “Voices” is one of his most widely known, one of his strongest poems. Like most of the Alexandrine’s works, it appears simple, seemingly moving in a single layer, but this will only fool those who have not yet been initiated into the deepest recesses of Kavafis’s poetry. The poem is actually open to multilayered interpretations and even philological studies. You need only pay attention to the final line and the punctuation - commas (ypostigmai, in philological terms) follow every word, expressing the sound of music breaking the nighttime silence. And these same commas will guide a knowing reader’s reciting voice to follow the pauses and gradually lower its tone to match the diminishing, fading sound.

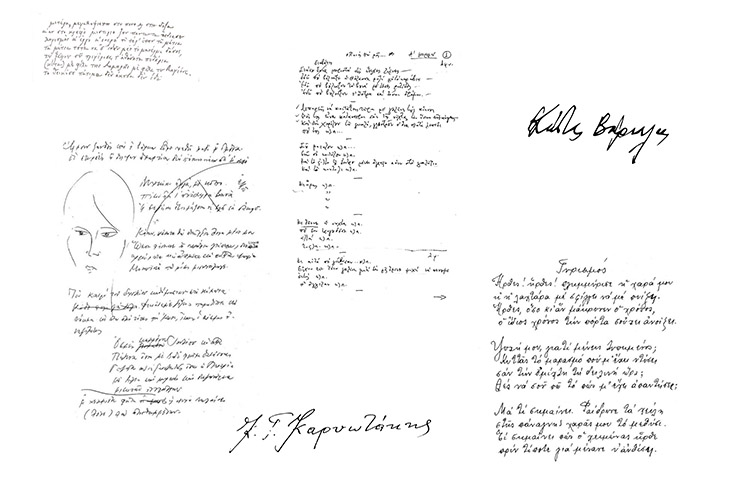

This poem, this nine-line poem (for the title is, of course, a line in itself), will take the perfectionistic Kavafis about nine years to complete and publish. If you happened to see the original composition, you would instantly understand why. That first poem, titled Phonai (archaising Greek spelling of “voices”) and written in 1894, is a dry, inert creation in a rigid archaising language, and every lyrical quality in it seems fake, made of lifeless material. Over the course of these nine years, the transformation will be impressive, as will be the final result. However, we would go completely off target if we were to further analyze this evolution, which is nonetheless of tremendous literary and philological interest.

Kavafis’s “Voices” is one of the most characteristic examples, (at least in modern Greek poetry), that demonstrate the occasional confluence of poetry and music, the affinity between those two fine arts, their relationship which, when successful, acquires an existence of its own and gives rise to a unique, self-sufficient result. Here we should note an important detail: Kavafis isn’t concerned with this subject, namely the relationship between poetry and music. And yet, unwittingly, he reveals it, he unconsciously sheds light on it.

Examine the vocabulary - “voices”, “sound of”, “sounds”, “music”, “hears”, the poem is laden with music-related words. Look at the final two lines, how in Kavafis’s conscience “our life’s oldest poetry” (this first, virgin poetry) becomes entwined with the music, that vague melody, obscure and gradually fading, as every virgin, vibrant thing is destined to fade away with the advent of maturity.

The common grounds of music and poetry

We shall not resort to banal statements to prove the relationship between music and poetry. For my part, I believe this relationship to be self-evident. A mere foray into the poetic texts of antiquity will suffice to reveal the intrinsic connection between lyre and lyricism, the etymological relation of the words, poetry’s priority over prose, rhapsody and the like. And these are just examples from Greek antiquity, other cultures can offer many more.

The present text would become nigh impossible to read were we to delve deeper into the linguistic phenomena concerning melody. We will instead limit our analysis to simpler phenomena, for instance the way linguistics describe the term “stress” and its corollary, “intonation”.

Stress is a phonological phenomenon that highlights one of the vowels of a word, setting it apart from the rest of the vowels in that same word. There are two types of stress, dynamic and musical. Dynamic stress means the stressed vowel is articulated with greater emphasis compared to the word’s other vowels, while in languages using musical stress, stresses are characterized by the rise and fall of the speaker’s voice. (Text in bold added by me).

To put it simply, simplistically even, so it can be understood by everyone. When language needs to escape the mundanity of everyday life, when it wishes to express intense emotion, joy, sorrow, pain, anger and the like, it begins to overlap with melody, rhythm, music. And it is at this meeting point, at the intersection, that a common terminology arises - meter, rhythm, stress, words shared by both poetry and music.

Poetry set to music, profit and loss…

For most people, the most telling example of an intersection between poetry and music is when the former is converted into song by the latter. Most people also believe that this cooperation is much more successful when the poem rhymes, when it’s easier to digest, to remember, even memorize. There is a grain of truth in this established belief. However, there is also a trap leading to what we call ease, shallowness, abuse of the verse. This view directly pertains to the matter of quality, both of the verse and the music it is set to.

Let us take a first example. Elytis completed the “Axion Esti” in 1959. It is a poetic composition of mixed verse structure, meaning it alternates between rhyming and free, yet strongly rhythmic verse. A tough poetic work composed in a tough time. The book’s sales are disappointing up to 1963, when Theodorakis presents his musical composition based on the poem. Book sales soar. And suddenly, a poem that was incomprehensible to most people is open to everyone, and even literally or poetically illiterate people are now singing the following lines.

Immaterial sun of justice

And you myrtle of veneration

don’t, please don’t

forsake my homeland.

You can see here how the ease of rhyming is proven false. There are even poetic “faults” in the verse, for example the enjambment in the third line, there is no rhyme, and yet this poem’s setting to music has given us one of the most seminal works in modern Greek music history.

A second example that will prove helpful in drawing our final conclusions on the meeting and intersection between music and poetry is once again a song by Theodorakis, this time an adaptation of Seferis’s “Denial” from his inaugurating poetic collection, “Turn”. The lines are, naturally, known to everyone.

“...With what a breath, with what a heart

passion, desire and pain

we lived our life; in vain!

And so we changed our ways…”

One of the most characteristic examples of poetic and linguistic exactness is that celebrated semi-colon in the third line. Seferis’s fear for its interpretation is known, as is his request that Theodorakis have the singer pause at this point. Theodorakis tried, but the very rules of music did not allow it. This creates a paradoxical result. The poet wrote the lines to express a specific meaning, yet the people who sing the poem have a completely different meaning in mind. Or you could ask if you like one of those who sing the Axion Esti - what does “immaterial sun of justice” mean? Chances are you won’t receive an answer. And yet, this line can be incorporated into the musical aesthetic of even those who are oblivious of its deeper interpretation.

Therefore, I think there are two important conclusions here. The first one concerns the quality of the two arts trying to merge. In order for it to be a successful union, a successful result, both parts must be possessed of excellent quality. No musical theme, no matter how good, can fix bad poetry, and no melody can be augmented by a worthy verse. There are plenty of such “contrary to nature” examples, now resting on the dusty shelves of music shops.

The second and most important, in my opinion, conclusion. The union of poetry and music doesn’t keep the autonomy of the parts intact, but creates a new, autonomous, self-sufficient result, largely independent of the creators’ original intentions. This transformation mostly and usually weakens the poetic work, as it is the most demanding to understand and digest. At the same time, it is most susceptible to variation. There are thousands of songs that have retained their melody with the passage of time, and as many poems whose lines have been corrupted over a very short period.

Is the produced work’s autonomy so full as to constitute a tenth art? Experts are negative in that respect, since the result of this union, try as it might to assert independence, remains unoriginal, it is still based on and born of already existing materials. This question is nevertheless somewhat academic in nature and isn’t all that essential. To be fair, the conjunction of fine arts is a difficult, challenging matter and tremendous abilities are required to ensure none of the two parts is wronged in this union. There are thousands of literary works that were corrupted by the seventh Art, and only a few that managed to overcome the power of the text. As we’ve said before - literature and especially poetry is always the weakest link when meeting another art.

…And poetry refusing to become song

However, there’s always a however. Can every poem combine with music, merge with it, producing a robust result? Are there any texts possessed of such unbridled autonomy as to render any attempt at coexistence with other arts impossible? And, vice versa - are there any musical creations capable of reaching greatness all by themselves, without even a good verse adding anything to their worth?

I will only answer on behalf of the poetry known to me. Yes, there are poems (always referring to modern Greek poetry) which are impossible to set to music or, to put it another way, for which any attempt at merging with music would destroy their meaning. This statement may sound absolute and may very well remain so, at least until a composer is born with that kind of exquisite, original and extraordinary abilities.

Papatzonis is impossible to set to music. Karyotakis, extremely hard. The same goes for a large part of the work of Elytis. And for the prose of Ritsos. Zervos is out of the question. It might be possible for some of Patrikios’s poems, albeit with much caution. Anagnostakis? Only for a few of the poems he wrote under an alias, for his deeper works demonstrate such a complex line structure it would prove too much even for the best composer. Palamas and Solomos are easier, mostly due to their rhyming verse, however the composer would have to resort to incorrect intonation and alterations to create a balanced result. As for Leontaris? He is good for ballads, but the ballad is a difficult genre, and it would need to remain “behind” the poem for a successful result. (Even when Arleta succeeded in setting Mist to music, she was forced to “sacrifice” the poem’s best stanza for commercial reasons). Kavafis? Negative, yet for an altogether different reason. Such is the dramatic quality of the Alexandrine’s poems, such is the power of his visualization, that we can consider his verse as already combining the two arts.

If this absolute statement is true, we arrive at yet another conclusion, treading carefully of course; after all, philology and music aren’t mathematics, with their axioms and certainties. When a creation rises above the common measure, when its quality surpasses the widely known and accepted standards, then its autonomy and solitude increase. We shall try to frame this differently. The more unique a poetic work, the deeper its meaning, the more distant the possibility to combine with music, for such a combination would compromise its depth and quality. I assume that the same conversely applies to music.

And herein exactly lies the ancient problem. Is setting poetry to music beneficial for it? Does a composer have a right to popularize their own interpretation of a poem’s meaning? Would it not be better, (and this is the argument put forward by most), for the lines of Elytis or any other poet to escape the confines of a secluded elite and become accessible to thousands or even millions of people?

A major question, which unfortunately diverges from the field of the two fine arts, carrying this consideration over to the sphere of general education, poetic and musical training. And even though I have been criticized for my opinion, I will repeat it - good poetry, like good music, requires an educated audience. One won’t love opera the first time they listen to it; to the uninitiated, its sound may even seem unbearable. One does not seek to become acquainted with poetry through Papatzonis or Elytis, for then they probably won’t get their hands on another book of poetry ever again. To appreciate the most worthy and excellent works these two fine arts have to offer, an education is required, not just in the strict sense of the term, but mainly through the formation of social references promoting quality, worth, critical thinking. An “educated” reader is capable of both interpreting Elytis’s meanings and appreciating the result of his poetry after it has been set to music, without downgrading the quality of any of the two works. They can tell the musical motif apart from the verse and evaluate each of them separately.

The death of critical discourse

The latter reasoning leads us to the great issue plaguing Art today, which is none other than the virtual abolition of critical discourse, and especially criticism. Any kind of judgment is now forbidden, the sole criterion is individual, personal, what we obscenely term “taste”. Absolute subjectivity. If Pound or Karyotakis are not to my liking, then all the worse for them. If Bach is detrimental to my good mood, there’s no way I’ll try and understand him. Elytis is good enough when accompanying Theodorakis’s music, but there’s no chance I’m buying his poetry and wasting time puzzling over it.

An entire society, (and among them, unfortunately, many “intellectuals”), have spent many years trying to enforce this dictatorship of personal taste. This egotistic view of Art. And they were victorious. If a new Karyotakis or Seferis were born today, and their verses were uploaded on the social networks, or even managed to get published, rest assured that no-one would be capable of telling them apart from mass-produced rhymes. As for music, whose intake is much more direct, anyone choosing to present anything more demanding than a mainstream song is sure to end up performing at some tiny, underground venue.

In a recent essay titled “The co-neighbours of national melancholy”, I wrote that there were only three people, from different fields of Art, who ever managed to understand the vanity of perfection; these were Hatzidakis in music, Horn in theater, and Karyotakis in literature. When Hatzidakis in an interview devalued the “easy” songs he had composed for the cinema, which we consider masterpieces, he didn’t do it out of elitism or pretentious humility. He did it because he had come face to face with his art’s chaotic world, its deeper qualities, its demands, its grandeur. Acting as his own personal judge, he understood that the path to greatness, worth, excellence, runs on endlessly, it is inexhaustible, and after a few years any attempt will prove insignificant, incomplete, obsolete. The martyrdom of Sisyphus, a never ending labor that gnaws at the creator, making them feel worthless and petty before their own work.

Setting a poem to music isn’t of course the only connection that can be established between music and poetry. We have to understand that remarkable art cannot fit in boxes, it cannot be confined and its influence knows no limits. Interaction is a daily occurrence in the field of arts. The composer sets a particular poem to music because its lines have goaded his creativity, awakened something, inspired him in some way. A poet’s triggers work in much the same way. In the past, when there was a shortage of technical means, poets would converse with nature and its sounds, they would listen to the songs in the alleys of every neighborhood, pay attention to their idioms, draw inspiration from every kind of sound, from every emotional expression. Today I know many who cannot even start writing before a musical composition has triggered their conscience and emotion.

Educated people who spend their entire lives striving for a better aesthetic result have the ability to draw upon neighboring arts; a painter draws upon music, a poet gets inspired by beautiful choreography, a sculptor by a fine poem. This ceaseless interaction has given rise to works both great and polysemous.

Lastly, there is the environment, the time, the given education, the given standards of a society. Greek society was never particularly friendly towards any kind of Art, and I don’t necessarily refer to periods of political instability, when every spiritual pursuit was seen as intrinsically hostile to authority. I refer to society en masse. You only have to look at the otherwise remarkable comedies of black-and-white cinema.

The poet, the composer, the painter, the dancer, are nothing more than caricatures of poor, nearly impoverished people living on other people’s charity. The poet is forced to write lines for school events, the composer is pressured to abandon classical music and work at a popular tavern, the painter is hired to design a shop’s sign in exchange for a meal. Indeed, the exaggerations notwithstanding, this depiction isn’t too far from reality. I’m not exactly sure if the reason is that the country never experienced an enlightenment of its own, if it’s the long enslavement to oriental leisure, or the echoes of German occupation.

The important thing is that, in Greece, the arts (and, naturally, their artists) are going through a peculiar exile, a special kind of alienation. They are tolerated as long as they serve the establishment, earn Nobel prizes, or otherwise function within the acceptable social framework. And, even more importantly - education and the whole of society are never instilled with a different aesthetic, with different priorities. What would our society look like if Karyotakis’s poetic condemnation of the petite-bourgeoisie was taught in schools? What kind of citizens would there be in twenty years’ time, if schools were to replace Palamas’s lackluster and dull poems with his line “...Shame, ever the shame of fatherlands…”?

Wouldn’t we be more reconciled and at peace with the idea of death and decay if Papatzonis’s more profound poetry was touched upon in the final years of high school? And wouldn’t our society be much more “enlightened” in a few years if art in general, instead ofhaving the, instead of status of a hobby or income-complementing activity,was considered a foundation for shaping consciences, developing critical spirit, fostering deeper thought? had the power to shape consciences, develop critical spirit, foster deeper thought?

A bit more, let us rise a bit higher…

Let us take some time to talk about the obvious, that none may say we are making light of it. Despite their differences (and there are lots of those), poetry and music are both striving, taking different paths and using different means, for the same result, namely the relief of the primordial fear of death and decay. Aesthetic pleasure is another goal, of course. As is the expression of the most original, most profound emotions. They are chaotic fields, before which every creator seems small and awkward.

One may ask, and rightly so - what about entertainment? What about recreation? Are we to spend our entire lives philosophizing on the lines of some poet or other? Or are we supposed to have fun listening to Beethoven, Bach and Antonioni?

Of course not, we simply have to know and discern different qualities, being aware of their special gravity. Of course we’ll read romance on the beach, the whole problem arises the moment we believe that this is good literature, that this is all literature has to offer, that these are its limits. It becomes a problem when we believe the guttural singing at the waterfront clubs is the music we deserve. When we make no attempt whatsoever to explore qualities that can console us in a much more worthwhile way, and also make us think and offer answers to life’s great questions. In other words, the problem arises when our aesthetic is compromising the level of worth, to the point where it banishes everything profound, fine, tasteful, fragrant, beyond the bounds of everyday life.

Naturally, we are probably struggling in vain. A huge majority in Greek society has already decided they are above the profound, choosing the two-dimensional, shallow, worthless and palatable instead. Anything requiring effort to approach and understand is expelled. Anything not serving personal interest and the economy is confined, drained, bled dry. A new mobile phone or car model is vastly more important to life than knowledge, education, aesthetics, behavior and politeness in a public space.

And yet. There has never been a society or a time in History where consciences were shaped by material means, no matter how developed or perfected. The shaping of the conscience has always been the job of education, culture, good writing, good music, art. Build modern school buildings, fill them with computers and all sorts of modern equipment. Of course we should, of course it is necessary. If, however, we don’t also fill them with passionate teachers, if our society does not decide that mind comes before matter, then we will just have spent money, and money is all we are getting back.

I will conclude this text with a poem by Polemis. He isn’t one of our most celebrated poets, the poem itself is far from excellent, its allegory is rather forcibly introduced, and its final stanza relapses into banality instead of elevating the poem. However, it expresses, in the words of a poet from another time, all but forgotten today, the relation between words and musical sounds, the power of poetic image, the education of the poets of old, even the less talented ones. In spite of its faults, the poem is characterized by fine technique, a twelve-syllable verse, a good meter and rhythm. Ritsos had stated he was greatly influenced by this poem. I can understand why, and there is plenty to say on the matter. But we shouldn’t digress into further poetic analysis, maybe this is a subject for another essay. And do not scorn older poets, they are not as old-fashioned as you might think, they are far from obsolete. With a bit of effort, you can find delight in their language, meaning, aesthetic, rhythm and symmetry.

The old violin

Hark the eerie ancient violin

in the silent April night

in its corpse, a soul is singing

through pale and ageless lips of love.

And the sleepless, envied nightingale

was hushed at once and stood in envy

seeking to see what bird was singing

a sweeter song of heart’s desire.

Even the graceless, timid scops owl,

shakes his wings in secret yearning

harks in silence the old violin

to learn, the poor soul, how to sigh.

What if it’s eaten by the woodworm?

What if the years are passing by?

Its voice gets sweeter, fairer, louder

it's aging well.

It’s me, the eerie ancient violin

in the silent April night

in my corpse, a soul is singing

through the fresh lips of my bloom.

What if the woodworm bites my innards?

What if the years run on forever?

My love gets sweeter, fairer, louder

I’m aging well.