Introduction to Modern Greek Poetry

However, if in this life, you seek something more than money and mere passing, this poetic journey becomes a one-way road. There, you will find the best answers to the eternal questions posed by humanity for countless centuries.

And, most importantly, there is a strong possibility (indeed, a very strong possibility) that your soul's anxieties will subside, allowing you to accept the finite nature of human existence much more easily. And most importantly, your conscience will rise tall against all the darkness and absurdity of this world. And as I wrote in another text, this entire mixture that poetry offers is not insignificant; it is substantial. Manos Tasakos

Let's make it clear from the beginning - this text is not an academic or even a philological work. Despite the fact that modern Greek poetry, which is indeed interesting today, spans only a little over two centuries, a scholarly study would need to include texts from the Byzantine period and pre-revolutionary times, as well as folk songs. However, what interests us today is to provide a first (and necessarily concise) answer to the extremely common question - 'How can I approach modern Greek poetry for the first time?' And of course, anyone who asks such a question cannot embark on their journey through verse with Falerius, Bergadis, Sklavos, Riga Feraios, Kontaratou, not even with Erotokritos or Digenis Akritis. All these poems, theatrical or prose, certainly have their value, but they are only suitable for those who have a solid poetic, philological, and broader literary education.

In this sense, the present text could be titled 'The First Encounter with Modern Greek Poetry,' a study guide, in essence, which includes the best and most notable poems in modern Greek literature. For this purpose (and as the text is primarily addressed to those who have had no previous contact with verses), beneath the names of the mentioned poets, there are also some initial suggestions for reading their best works. Most of the proposed poems belong to poetry collections that are not mentioned here, but today, with the ease of the internet, you can easily discover them. Finally, in order for all this to be accessible to the last reader, we will avoid philological terminology, at least as much as possible.

The Starting Point

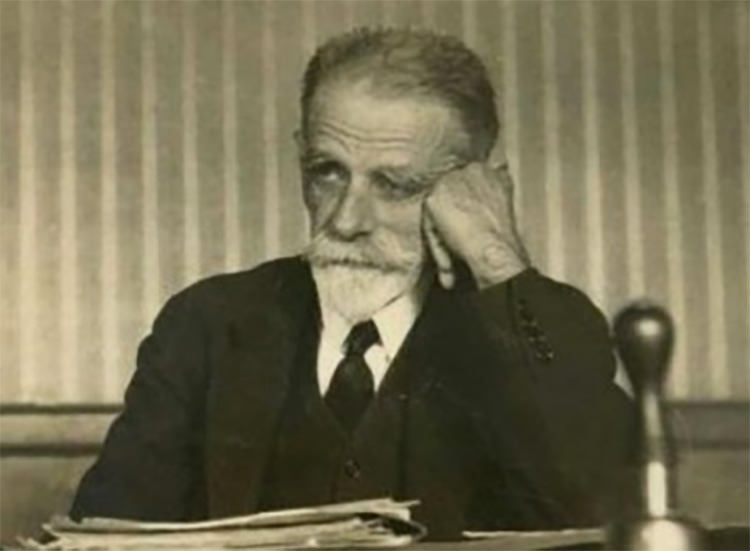

Image 1. Dionysios Solomos, the true father of modern Greek poetry. There are several poetic texts before him, but they do not constitute a unified poetic body, and their content is not easily approachable by today's readers.

So, let's follow the beaten path and place the starting point of modern Greek poetry in the Ionian School and, to a lesser extent, the Athenian School. What does all this mean in simple Greek? For the Ionian Islands, the answer is easy and probably well-known. Solomos and Kalvos stand out in the top positions, without underestimating Laskaratos, Valaoritis, and many other mainly 'Solomian' poets. Around the same period, after the revolution, in the first Athenian School, we have Soutsos, Rangavis, later Vizyinos, Paraschos, and Provelengios. Let's focus on this period for a while.

Naturally, the themes of this period revolve around the revolution, personal heroism, national catastrophes, battles, and generally the liberation of the country. The long struggle leaves no room for introspection (despite similar attempts in Kalvos and some Solomian works) and certainly not for purely existential poetry. Apart from the revolution, there is (mainly in the first Athenian School) a lot of nature, a lot of verve, refined melancholy, and often verse devoid of content.

For those seeking the most worthy representatives of this period, reading Solomos is a one-way street. One could say, not so much for the content (although it is highly valuable), but for the mastery of verse, its plasticity, and the extremely successful use of homoioteleuton (even though Solomos' Greek was not among the best). However, here we have a folkish (with certain admixtures), internal rhythm; there is genuine emotion and, in general, exceptional poetic moments (such as the poem about the destruction of Psara). Especially for those who want to start writing poetry, reading Solomos is a prerequisite. I'm writing this as simply as possible; it's not the time to get entangled in the metrics of verse, the rhetoric, or even the weaknesses in Solomos.

(The Cretan, The Lambros, The Free Besieged, and The Porphyra are the most accomplished works of Solomos, certainly The Destruction of Psara, The Funeral Ode (a and b), The Cemetery, and, of course, some verses from the Hymn to Liberty. The latter is, if I remember correctly, a monstrous work of 158 stanzas with significant disparities in technique and content. Most of Solomos' works are incomplete, which has sparked many controversies among philologists and critics. However, if you decide to purchase The Complete Works of Solomos, make sure the edition includes, without fail, the prefaces by Jacob Polylas, which, despite their positive predisposition, provide one of the best critical presentations of Solomian works.)

With Kalvos, we certainly face a problem. The foolish language conflict has disconnected at least the last four generations from the simple Katharevousa, let alone the heavy (often archaic) language of Kalvos. Despite this, I would suggest not getting discouraged and persisting in reading his works. He is a unique poet who was fiercely opposed by the Greek side, especially his fellow countrymen. What we receive is that even Solomos' behavior towards him is extremely cold. As evidence of this, Kalvos remains relatively unknown to the Greek audience, at least until 1889 when Palamas brings him out of obscurity with a speech published in the Estia magazine. Dimitris Vikelas preceded him just a year earlier, but the influence of Palamas embraces a much broader audience. Certainly, the approach to Kalvos' (small) body of work is worthwhile." "Even if sometimes guidance from a dictionary is necessary."

(From Kalvos, do not miss the poems "O Philopatris," "To the Sacred Battalion," the exceptional "To Death," "To Freedom.")

The Turning Point of Palamas

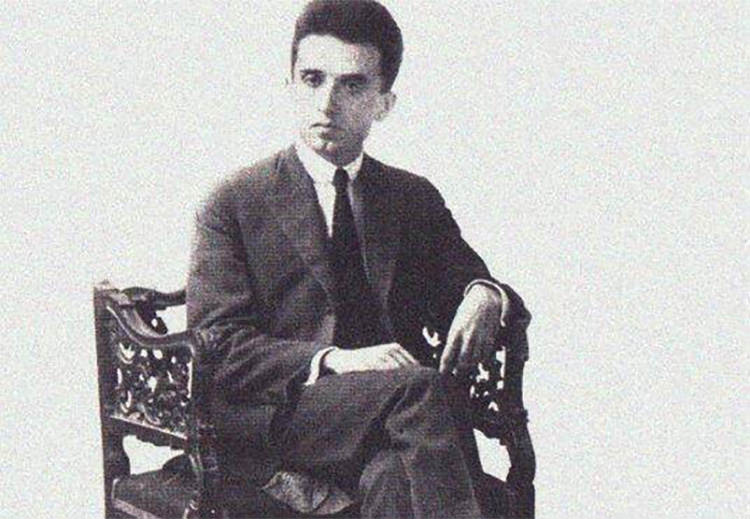

Image 2. We owe a lot to Kostis Palamas. It's not just his exceptional demotic language or the fact that he brought poetry down to everyday life. It's also his daring, almost anarchistic verses that unfortunately remain unknown to the public.

The first major turning point in modern Greek poetry comes with the emergence of Kostis Palamas. Poetry descends from the clouds for the first time and deals with everyday life, human struggles, and existential problems. Palamas is undoubtedly a threshold, and therefore his work is not devoid of vigor, grandiloquence, and conflicting messages. His themes cover a vast range, from the Greek Revolution to the Twelve-Lettered Alphabet of the Gypsy. There is an exceptional variety of content and meaning; Palamas resembles a huge plate filled with verses, from which everyone chooses according to their own criteria. He even wrote a poem about Oriental songs.

This chaotic poetry also contributed to the "educational exploitation" of Palamian work, although in schools, only his least painful and most patriotic poems were taught. This, in turn, resulted in Palamas quickly transforming into a painless, anachronistic, and often boring voice. Unfairly so, because Palamas has written exceptional verses filled with doubt, reflection, intellectual depth, and even an anarchic disposition. He is undoubtedly a prolific writer, but in this way, he enriched modern Greek literature significantly, and as a bridge between two eras, he helped poetry become deeper and more spiritual. Worth mentioning is Palamas's language, which exploits the richness of the demotic and imparts an unfamiliar warmth to previous poets.

(Palamas's work is vast, and it is almost impossible to present here its best moments. Merely as indicative examples, we will mention "The Chapel," "To the Island of Kleisova," "Dawn," "A Bitterness," "The Song of the Madman," "The Journey is Over, We Have Arrived," "The House Where I Was Born," "Love and Revelry," "All Fires Are Extinguished" [the first part is exceptional], "Child, My Garden," and definitely "The Twelve-Lettered Alphabet of the Gypsy." In most of these poems, especially in the Twelve-Lettered Alphabet, you will find that the "school" Palamas has nothing to do with his most deserving and daring poems.)

Cavafy, Karyotakis, and the Generation of the 20th Century

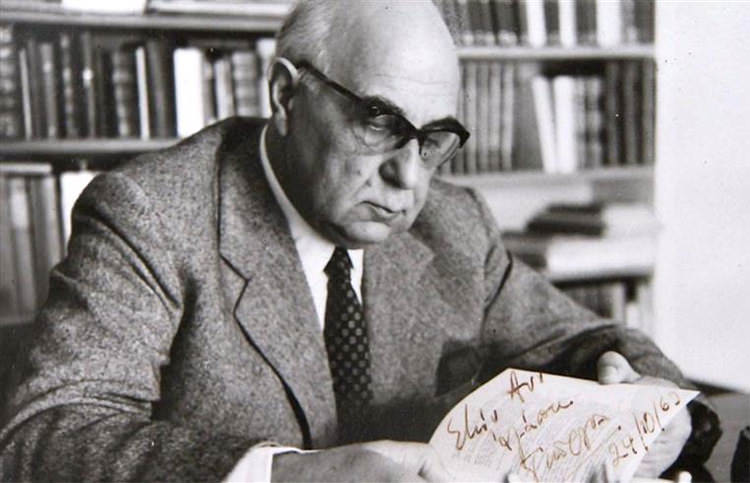

Image 3. The great turning point and the great leap in modern Greek poetry. Prominent, revolutionary, and perhaps the only one who quickly grasped the root of evil, the Greek petit-bourgeoisie.

If with Palamas, modern Greek poetry becomes imbued and begins to convey timeless and universal messages, with Karyotakis, verse definitively distances itself from the contrived, the melodramatic, and the saccharine, and acquires a unique power, one could say unparalleled to this day. We need to dwell a little longer on this point.

The Generation of the 20th century, where Karyotakis is the leading figure by a large margin, is the most underestimated and perhaps the most unjustly treated in the history of modern Greek poetry. Firstly, it was mercilessly struck by reality itself. Tuberculosis, various illnesses, suicides, poverty, deprivation, and every imaginable misfortune almost decimated it. But even without all that, the era itself exudes misery, decline, and unhappiness, characteristics that intensified with the Asia Minor Catastrophe. Don't laugh and don't believe in the myth and the lie that was built around Karyotakis; he was not a pessimistic poet himself, nor was there any gene that led him to suicide. It was the black and dark reality, the repulsive environment, and the petty-bourgeois morality that began to assert itself dynamically in the country.

Karyotakis represents the second major turning point in modern Greek poetry and forever changes the poetic language and thematic content. This is excellently reflected by Tellos Agras in the best critique of Karyotakis to this day: "... Karyotakis surpassed us all immediately and continuously...

In reality, it constitutes a unique milestone in poetic history, as there is no subsequent poet (with the exception, perhaps, of Elytis) who has not been influenced by Karyotakis. Ritsos, Vrettakos, Seferis, and hundreds more followed in his footsteps, especially in their early poetry collections.

However, Karyotakis and his generation were fiercely attacked by the literary establishment. He was neither wanted nor supported by anyone, with very few exceptions. The Left of the time considered him defeatist and decadent, while the influential critics (such as Dimaras, for example) even questioned the poetic value of his work. The upcoming generation of the 1930s exiled him completely from poetic history, despite his suicide occurring just a year before in 1928. Karyotakis was marginalized then and continues to be so today. His criticism of petit-bourgeoisie and insignificance is unforgivable to many. Nevertheless, a hundred years later, he remains relevant, timeless, and above all, revolutionary.

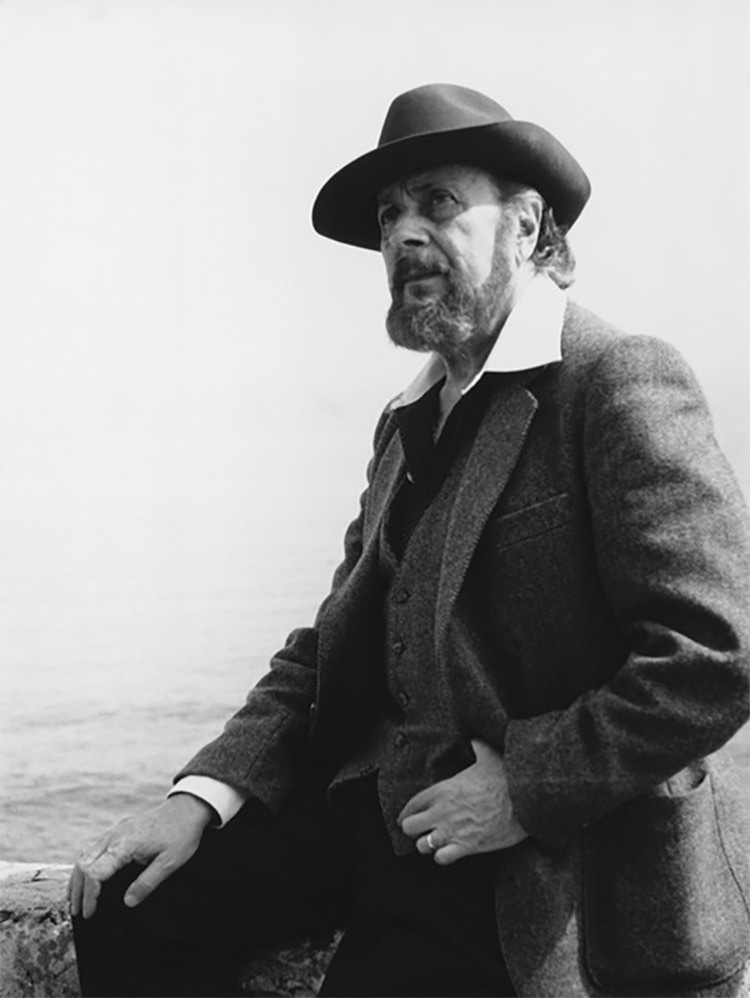

Image 4: Konstantinos P. Kavafis, a category of his own, his poetry could fill the subject of an academic chair. Even today, he is misunderstood and misrepresented by many.

A few years before Karyotakis's suicide, in the early 1920s, another major turning point in poetic history began to emerge in Athens, Constantine P. Cavafy. Similar to Karyotakis, his reception was lukewarm at best and outright hostile at worst.

Hostility is the only characteristic he shares with Karyotakis because, otherwise, his poetry emerges from completely different paths and utilizes entirely different expressive means. Cavafy, who was concise and Doric, and Karyotakis, who was dramatic and Ionic, nevertheless, arrive at the same conclusion in terms of meaning: to live and die with a clear conscience. The established poetic establishment in Greece, almost completely ignorant of Cavafy, ignores him, and even Palamas himself is dismissive of his poetry. Only a few discern his qualities, but it will take years for his recognition, not only in Greek but also in the global arena.

(Read all of Karyotakis, read all of Cavafy. Firstly, the poems of both are relatively few. However, even the weaker ones have their value. For someone truly seeking to comprehend modern Greek poetry and approach its greatest representatives, reading the complete works of Karyotakis and Cavafy is a prerequisite.)

The forgotten Takis Papatzonis.

Image 5: Takis Papatzonis, the most intellectual among our intellectuals. A unique example of a top poet who remains in the margins and in oblivion for extraliterary reasons.

It is evident that in Greece, exceptional qualities are exiled and fought against. A characteristic case is that of Takis Papatzonis. He was among the first to write in demotic Greek (since the 1920s), yet most ignore him and give credit to Seferis. He lived much longer than Karyotakis and Cavafy, writing poems with profound spirituality. Some of his works could be described as small philosophical essays, yet no generation wants him among its ranks, and no leading poet has the magnanimity to recognize the exceptional quality of his work.

On the contrary, a critical review by Papatzonis of Seferis's "Turn" will make him a target of the Seferian circle, and even the insecure Seferis will never forgive him, even when their relationship somewhat improves after years. Another injustice in the history of modern Greek poetry, as Papatzonis stands at the same, if not greater, level as our other leading poets. Even today, when we search desperately for a good verse, a worthy poem, Papatzonis remains unread, unappreciated, and incomprehensible. It is true that his poetry is difficult. Someone uneducated in poetry, let them be the last in reading it, understanding it requires a great familiarity with poetry and literature in general.

(Papatsonis, [you will find him mostly as Papatzonis, he himself confessed that he preferred writing with "z"], has also written poems that are more accessible to the average reader. Before you delve into the more demanding ones, do not overlook his poems "The Paragoula," "White Greek Deserted Church," "No One Remained Unaffected," the masterpiece "The Grudge of Hades," and the equally masterful "In Myself."

However, the deeper Papatsonis is hidden in his other challenging poems, which you will gradually approach and decipher. Finally, one of the myths accompanying Papatsonis, which certainly contributed to his oblivion, is that he is a religious poet, a criticism that is precisely a myth. Simply put, just as Cavafy drew from history and reshaped his material, Papatsonis draws from the spirit of Christianity to pose or answer primordial existential and philosophical questions.)

This trio (Karyotakis, Cavafy, and Papatsonis) is at the forefront of modern Greek poetry. Their value is such that they are not easily classified; their names are usually absent from each generation's lists, as they are unsure of the criteria for classifying them and resist being grouped together. They are three unique cases that unfortunately are either not taught in philosophical schools or are taught with their poetry greatly distorted in meaning.

The notorious generation of the 1930s

Image 6: George Seferis, the informal leader of the generation of the 1930s. Several exceptional poems, but also excessive praises from Theotokas, Karantoni, Katsimbalis, and many others from his "circle."

Much has been written about the generation of the 1930s that follows, and even more has been distorted. No one can doubt its value and qualities, despite the exaggeration and overestimation by the Nobel Prize committee and many sycophants of the poetic "circle." Seferis, Ritsos, Vrettakos, and Elytis are undoubtedly among the peaks of this generation. They are accompanied by a significant mythology. For Seferis, we have been convinced that he stands in contrast to Karyotakis with a restrained optimism, nothing more fallacious than that; in his best poems, Seferis is dark, much darker than Karyotakis.

They attempted to classify Elytis among the surrealists, but his best poems are far from that specific movement. On a social and political level, the generation of the 1930s served as a resounding response and deviation from the anarchy, the revolutionary spirit, and the questioning of the generation of the 1920s. Despite its great value, with few exceptions, the generation of the 1930s remained systemic, respectable, within limits, and never reached the point of questioning the social structure itself, the root of petit-bourgeoisie, human weakness. Some poems by Ritsos and a few by Seferis are exceptions, with the pinnacle being "Theatre People, M.A." The radicalism that started fervently in the 1920s faded away in a short period with a poetry-response much more acceptable to the wider reading public.

Image 7: Yannis Ritsos, along with Palamas, the most prolific of our poets, but certainly outstanding. In his best poems, the influence of Karyotakis is clearly discernible.

The war and the civil war that followed would serve as excellent triggers for the emergence of one of the most significant generations in modern Greek poetry, the post-war generation, and especially the one characterized as the first post-war generation. The atrocities and horror of the war are still vivid, and poets such as Tasos Livaditis and Titos Patrikios, in their early works, almost exclusively deal with these dark images and experiences.

The era will give birth to many noteworthy poets of the first and second ranks. Gradually, all of them will move away from the memories of the war and turn to existential poetry with very good results. Until the end of the 1960s, the post-war poets will produce dense, profound, and uniquely expressive works, despite a few imitations in technique. Most of them will achieve a personal and recognizable style.

(The work of the generation of the 1930s is enormous, making it impossible to anthologize it in its entirety. I will limit myself to some truly masterpieces. From Ritsos: "Our House," "When We Reach the Edge of Silence," "Greek Coffee Makers," "Alone with His Work," "The Last Obolus," "The Standards," and of course, the majority of "Epitaph." From Seferis: the exceptional "Theatre People, M.A," "Denial," "The Well," "Our Place Is Closed [from the Novel, 1935]," a suffocating poem surpassing even Karyotakis in its dark and absolute tones, "Now That You Are Leaving," "The Return of the Exiled," "Helen." From Elytis: "Marina of the Rocks," "Birth of the Day," "The Mad Rose Tree," "Body of Summer," "Under the Daisy's Threshing Floor," "The Garden Merged with the Sea," and, of course, the majority of "Heroic and Funeral Hymn for the Lost Second Lieutenant in Albania," "The Orange Grove," "The Axion Esti," "Friends Came Dressed." From Vrettakos: "The Skylark of the Morning," "Elegy on the Tomb of a Young Fighter," "The Sad Song of My Youth," "The Child with the Harmonica," "Ode to Man," "The Crazed Horse," "Invitation," "Prayer.")

Decades in Review

Image 8 The most well-known edition by Estia of "The Complete Works" by Karyotakis. If you come across it, pay special attention to Agas's critique to understand its value in the past and how its disappearance is a significant loss today.

Next is the decade of the 70s, the generation that Vasilis Varikas named "The Generation of Doubt," a term that, in my opinion, is invalid and unsuccessful in its essence, as it is difficult to speak of a generation with common characteristics here, while the qualities are unequal and vary greatly among the poets of the era. Not to mention the fact that substantial and profound doubt is rarely encountered in this generation. However, there is no doubt that despite exceptions, the qualities in poetry gradually decline after the 80s.

Expressively, there is nothing new or groundbreaking; there is a great thematic repetition and, above all, an inability to express or even capture the characteristics and impasses of the present era. From the 90s onwards, absolute subjectivism prevails in Art, while any serious critical voice that could help in highlighting qualities has weakened or completely disappeared. There are good individual voices, but it is difficult for them to form a poetic body with distinct characteristics, while readers are becoming increasingly uneducated in poetry. Finally, the publishers' inability and indifference towards poetry have given space to self-publishing, allowing anyone to publish a poetry collection by paying a corresponding company. This new reality has made critical scrutiny and evaluation entirely impossible, intensifying confusion among readers regarding the value of poetic work.

This drought forces us even today to resort to older works, which, however, possess both power of content and exceptional technique, both in rhymed and free verse. There is no doubt that at some point, new sparks will give birth to new and good poetry, but Art does not obey human fragmentation of time. The emergence of new and worthy poetry can happen in two years or even in a century since it is History that largely determines its consequences and qualities.

Let's attempt a summary, always for those who want to initiate a deeper connection with modern Greek poetry. There are, of course, the prominent figures we have already mentioned, from whom one could embark on their exploration of poetry

—Solomos, Kalvos, Palamas, Karyotakis, Cavafy, Seferis, Papatzonis, Ritsos, Elytis, Vrettakos. However, among them, there are hundreds of others who may not have reached the peak of the poetic Kavafian scale but have certainly produced exceptional and worthy poems. Only indicatively, and without the criterion of generations, it is impossible to mention them all - Papanikolaou, Douatzis, Varvitsiotis, Dimoulas, Vakalos, Dallas, Fokas, Anagnostakis, Leivaditis, Patrickios, Karouzos, Katsaros, Malakasis, Sinopoulos, Theodorou, Vafopoulos, Fragopoulos, Leontraris, Sachtouris, Melissanthi, Agas, Fostiéris, Apostolidis, Valaoritis, Aslanoglou, Varnalis, Skaribas, Geralis, Hatzopoulos, Drosinis, Dimitriou, Zervos, Ioannidis, Karandonis, Karella, Lapathiotis, Montis, Schinas, Barlas, Panagiotopoulos, Sarantaris, Sikelianos, Takopoulos, Tryfonas, Christanopoulos, Gogos, Varveris, Kontos, Kontopoulos, and many others that I may have forgotten or are of lesser scope. In addition to all of them, several contemporary poets are still developing their work, which has not been completed or fully assessed.

The list is long, and it is certainly challenging to acquire the works of all these poets, not to mention that some of them, like Ritsos and Palamas, for example, extend to ten or twelve volumes in total. The best thing one could do when starting, at least until they begin to acquire poetic judgment, is to procure a critical anthology of modern Greek poetry. Pay attention, a critical anthology, which is compiled based on strict quality criteria and not based on the weight of History and the poetic value that has passed to our days.

A few more notes

Poetry, the denser and deeper form of language, certainly requires equally educated readers, especially in the knowledge of the entire language. The greater your linguistic proficiency, the easier it will be to understand the subtle shades in a poem, as well as its deeper meanings. Particularly in the case of older poets, nothing is accidental within the verse; not even a comma or a period. Everything signifies something, everything symbolizes something, everything conveys meaning. To comprehend what I am writing, let us examine a poem by Montis, short in length but profound in meaning.

"Now I want you, Uncle Kostas, who see yourself in invisibility, and Yiannakis (our Yiannakis, my friend!) on the surface!.."

Of course, we will not delve into the essence of the poem, which encapsulates an entire reality in just four verses. Just observe the absence of the final "n" in the verse and its repetition, "our Yiannakis, my friend!" Notice how the absence of one single letter neutralizes the subject and succinctly represents the insignificance of the person, the mediocrity, the absolute nothingness. This is one of the reasons why poetry requires active reading; it cannot be read "casually" as an accessory on the beach or as a lullaby in bed. Poetry demands our full concentration, our contemplation, and even our imagination to unlock its secrets.

Image 9: Kostas Montis, the best Cypriot poet to this day. He became known in Greece only in the last decade. He comfortably ranks among the top figures of modern Greek poetry.

Another point worth noting is that while Greece may not have significant novels, we excel in the short form, such as narratives or novellas, and especially in poetry. In just two hundred years of free existence, we possess many talented poets covering almost every subject.

In poetry, you will find answers (and, of course, many questions) about life, death, love, consciousness, the state, politics, society, friendship, maturity, old age, and many other topics beyond counting. Unfortunately, as the years pass, the voices that consider poetry superfluous, useless, and antiquated grow stronger. This view is even expressed by educators and philologists. Nothing could be further from the truth. It is certain that good poetry will eventually return with greater force, as it remains the only form of language capable of elevating, healing, and ennobling through its semantic power.

Of course, exceptional poems exist in all languages. However, unfortunately, poetry cannot be fully translated; at best, only the meaning of a poem can be conveyed. The mother tongue is irreplaceable in understanding poetry, especially in demanding works that employ subtle nuances, idioms, and polysemous words. This should not discourage you from reading foreign poets, as even in translation, you can grasp a deeper meaning. That is one of the reasons why modern Greek poetry rarely surpasses national borders, even when poets like Cavafy have been translated multiple times. His subtle irony or underlying critique cannot be adequately captured.

Finally, we must remember that until the 1970s, poetry held an exceptional position within the broader literary field. The quality of criticism and even the few readers demanded careful writing from poets, avoiding clichés and stereotypes. With this in mind, even if you come across weak poems by good poets, you have a minimum level of quality and intellectual depth. The prolific Ritsos, for example, has volumes filled with mediocre poems, yet even those will not offend you as a reader; they will not disappoint your expectations. Different times, different customs. Even the most insignificant or mediocre poets of that time possessed depth of reflection and intellectualism derived from extensive knowledge of language and broad extracurricular education.

Also, remember that even the slightest element plays a role in poetry, making it important to acquire editions that preserve the original writing. Most of the aforementioned poets wrote in polytonic orthography. Therefore, regardless of your beliefs about the language, it is advisable to seek editions that faithfully reproduce the original version. And for heaven's sake, avoid as much as possible the reprints on social networks; most of the time, they are filled with mistakes and omissions. Of course, as the lifespan of books on bookstore shelves becomes increasingly shorter, in many cases, you may struggle to find older editions, requiring several visits to secondhand bookstores, which fortunately still exist in relatively significant numbers, at least in Athens.

Beside you lies a spiritual treasure trove, not to mention ancient Greek literature. To embark on the path of selecting, reading, analyzing, and understanding modern Greek poetry will require a considerable amount of time. Even with the strictest selection, the collection of excellent poems exceeds four or five volumes.

However, if in this life, you seek something more than money and mere passing, this poetic journey becomes a one-way road. There, you will find the best answers to the eternal questions posed by humanity for countless centuries.

And, most importantly, there is a strong possibility (indeed, a very strong possibility) that your soul's anxieties will subside, allowing you to accept the finite nature of human existence much more easily. And most importantly, your conscience will rise tall against all the darkness and absurdity of this world.

And as I wrote in another text, this entire mixture that poetry offers is not insignificant; it is substantial.

Manos Tasakos - Short Biography:

Manos Tasakos was born in Athens. He started writing at a young age, publishing a local newspaper at the age of fifteen. He studied at the Law School of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.

From the "24 Grammata" editions, the following works are available in print: "The Mediocre Life of Alexandros Valetas," a novel from 2017, "Wild Herbs," a short story from 2018 (in the collective publication "Lathropsychoi"), and "Non omnis moriar," a short story from 2020 (in the collective publication "The Pandemic"). From Livani publications, the novel "The Death of Anna Vavaki" was released in print in 2021.

Apart from his contributions to literature, Manos Tasakos is also known for his critical work, which has been compiled and published in two volumes.

The website of Manos Tasakos is: www.tasakos.gr