Titos Patrikios

And so I no longer write

to offer paper rifles,

weapons of hollow, rambling words.

I seek to raise but a corner of the truth

shed light on our falsified existence.

As much as I can, as long as I hold!”Titos Patrikios

“The beauty of women who change life

is in the poems they inspired

evergreen roses, with the same perfume

evergreen roses, as poets always said”.Titos Patrikios

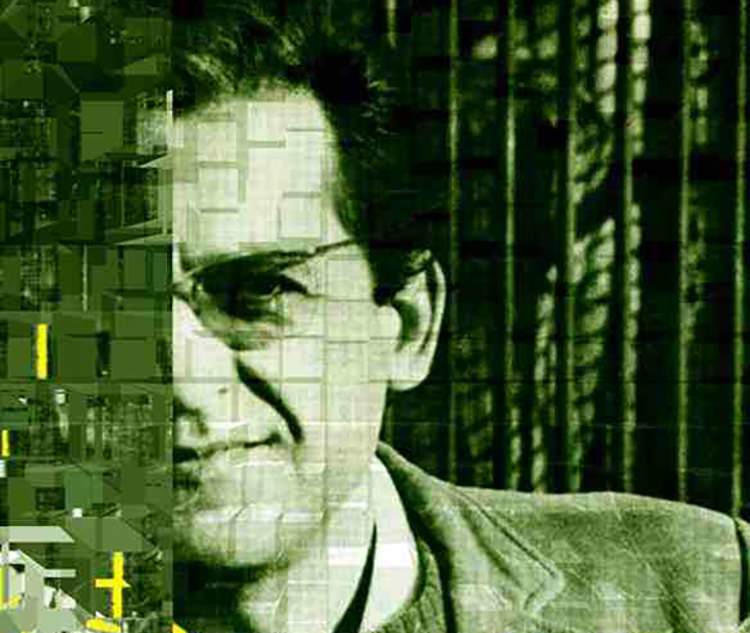

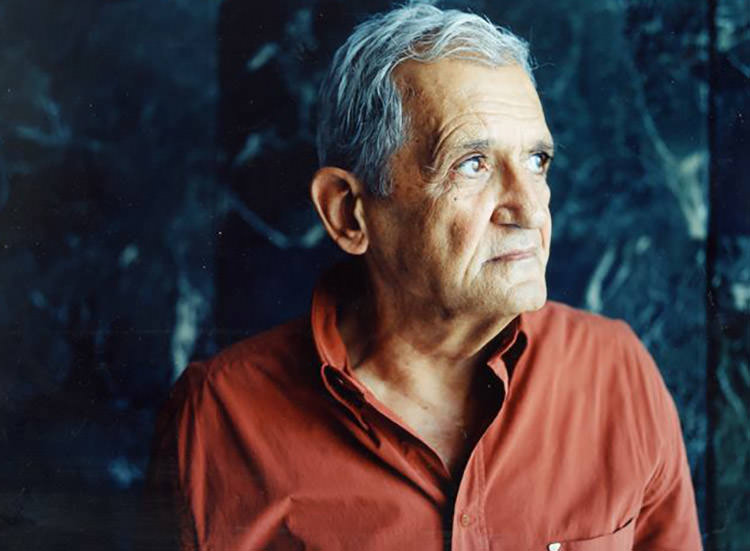

This April, we are especially glad and thrilled to welcome to Radio Art perhaps the greatest living Greek poet, Titos Patrikios. His life has been filled with adventure, twists, and great losses. He has had the courage to abandon ideologies, countries, situations, and begin anew. His poetry transcends the borders of art, it has the power to help readers discover their own existence and perceive the world’s unseen side, both essential to self-consciousness.

His work, poetic or prose, has always been deeply humane and insightful, searching for the truth in every era, masterfully grasping the heart of eternal poetry, love and existence.

When Titos Patrikios was 26 years old, Giannis Ritsos wrote a dedication to him saying that “his poetic star is destined to light up our sky”, and this was exactly what happened, his star will always shine next to Elytis, Seferis, Ritsos, Livaditis, and so many other brilliant creators.

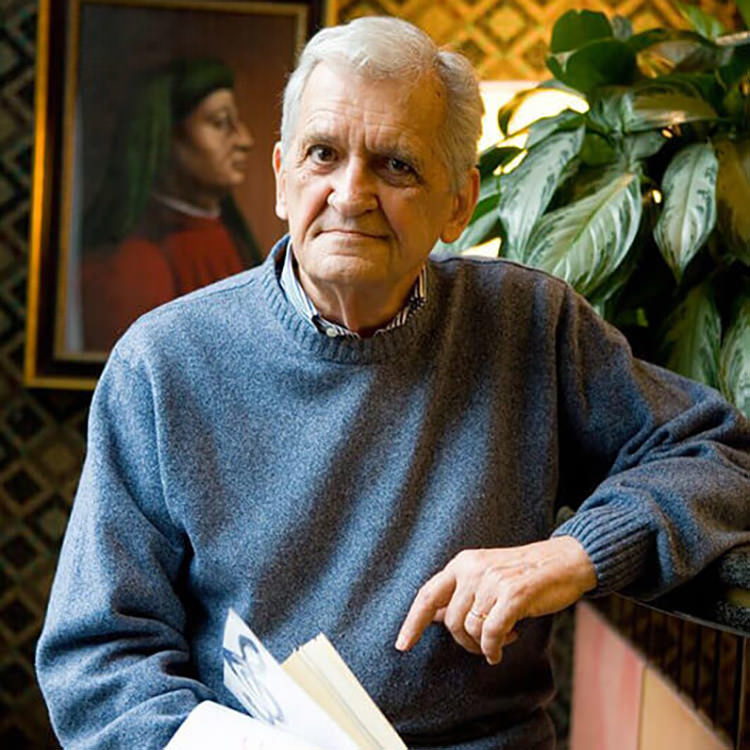

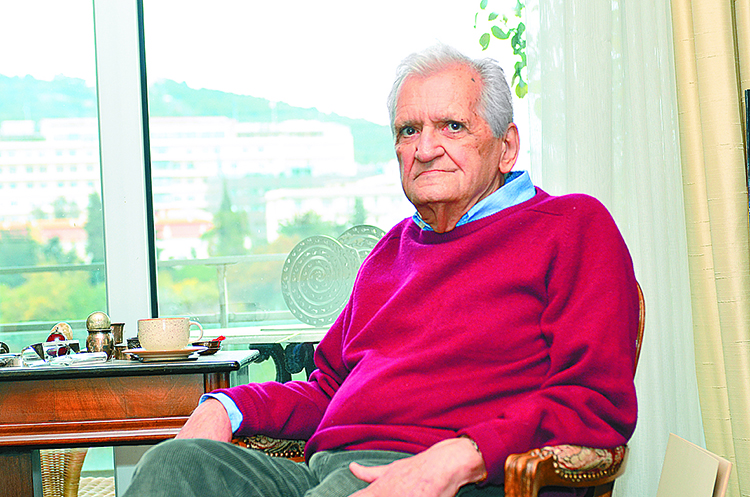

I had the pleasure of meeting the poet at his home and having a long, particularly interesting conversation with him. His complete mental clarity, boundless modesty and excellent physical condition revealed a thinker still capable of offering a lot.

Included below are a brief biography, my conversation with him, and a limited selection of poems I find especially moving. I hope you find them interesting.

L.M.: Dear Mr. Patrikios, welcome to Radio Art. It is our great honor and pleasure that you have agreed to this conversation. I am truly grateful.

T.P.: I’m grateful too.

L.M.: What are your views on today’s world?

T.P.: To be honest, I never expected to see Europe in another war, because I became too involved in the previous war, my experience was too bad, intense, and dangerous, and I thought we were done with that sort of thing. That our conflicts would at least be political and not military. And yet, it has happened again, and my only hope is that it doesn’t escalate further. But I can see there are uncontrollable powers, unrestrained. It is horrible.

L.M.: What of Greece in the midst of this upheaval?

T.P.: Thankfully, we have left the terrible times of memoranda and external control behind us. I hope we can move forward through the diversity of ideas, for this is what democracy is, as long as this diversity doesn’t lead to conflict and, eventually, disaster.

L.M.: Let us hope so.

T.P.: I hope so too.

L.M.: However, the cultural power of Greece is still strong, isn’t it? I’m talking about the intellectuals here in Greece.

T.P.: I think so. I wouldn’t like to say anything more, lest it sound pompous. But fortunately, cultural activity remains very much alive and, I hope, creative.

L.M.: In your book “the Temptation of Nostalgia”, you express the thought that “joy and loss, celebration and sorrow, we taste everything, but all mixed up and incoherent. Only art can give them to us in a concise, concentrated manner”.

T.P.: Indeed, and I believe this is exactly the role of art. Either the art of speech, the art of sound, or the art of design and color. The arts in general.

L.M.: Is poetry the beginning of every art, as some have said, or do you think this sounds a little extreme?

T.P.: I wouldn’t call it too extreme, but I believe that composing speech in the form of a poem also becomes a motivation for other forms of artistic expression. But visual arts are probably just as old. Just think of the findings in the prehistoric caverns at Altamira and other places, we can see that, from very early on, humans wished to reshape the world they lived in, either through speech or the performing art and music. Of course, at first, poetry was closely connected to music. Later on, the arts obtained autonomy, yet they never ceased to interact with one another.

L.M.: This is exactly what we are trying to do here on Radio Art, bring poetry and music close together. This is our main effort, for we believe it is a worthwhile endeavor.

T.P.: Of course it is, but painting is also closely allied to poetry.

L.M.: Indeed, we could say those three are sisters (music, poetry, and painting).

T.P.: Yes.

L.M.: Could we say that poetry, good poetry, has the power to help us discover ourselves and also enlighten our life?

T.P.: This is something I first said a long time ago: that while poetry may appear more like a self-portrait of the poet themselves, a study of their soul and social position, it ends up motivating readers to do their own autobiography. And so, when we read autobiographical poems written by great poets, we no longer care about the poet’s life, but about the fact that we discover…

L.M.: Ourselves.

T.P.: Ourselves, yes, and aspects of ourselves that were hidden until then. Aspects we couldn’t see. This means we are rediscovering ourselves in the world.

L.M.: I often think that the small things of everyday life can bring us great relief. This can be illustrated by one of your poems, of which I am particularly fond. I would like to remind you of it, you wrote it in Paris in 1960 and it is called “Underground Train”. Do you remember?

T.P.: Yes.

And the years shall pass

masses of mountain and stone shall block the way

all shall be forgotten

as is the everyday sustenance

that keeps us on our feet.

Everything but that moment

when in the crowded underground train

you held on to my arm.

L.M.: What a wonderful poem!

T.P.: It is a rendition of an experience I had in the Paris metro, but I have always been impressed at this poem’s wide appeal. I could never imagine. And I will recount one particular incident. Many years ago, I was invited to a high school in Italy, mostly for immigrant children from various countries. When I arrived, they gave me a present. A small album. It was this poem, translated into Italian. And these children had translated it into their own languages. They were from Morocco, Pakistan, Palestine, Africa, the children of immigrants, and they liked this poem. I was at a loss. I could never imagine something like that could happen.

L.M.: How would you explain this? Why is this particular poem so touching?

T.P.: What can I say? When a poet begins to explain one of his poems, that means the poem is not capable of offering answers in itself. What can I say?

L.M.: May I tell you why it is touching to me?

T.P.: Yes. I would find it really interesting.

L.M.: Because I can relate to it, and because it demonstrates that a moment - an incident - so small but tender all the same can create joy and a strong feeling of love to every person, especially simple, everyday people. I take immense joy in holding my wife’s hand. I believe this little moment can touch everyone, because it can happen to anyone. This is how I understood it, and this is why it moved me. It is an explanation, don’t you think?

T.P.: It is, and I’m glad that such a small poem, so short in length, is capable of creating that sort of emotion.

L.M.: It may be short in length, but it’s full of meaning.

T.P.: And of course, I gave it the title “underground train”, because at the time I was writing - for I wrote it in Greek, though in Paris - there was no metro in Greece. We didn’t even use this term. But if I were to publish it now, I would call it “metro”, not underground train.

L.M.: It doesn’t matter. It is still fairly relevant today. So, is poetry an ethics lesson? As Eluard had said?

T.P.: It is, but every ethics lesson harbors danger, the danger that the one teaching the lesson may wish to impose their opinion on others. So I would say it is a critical lesson. An ethics lesson, not an ethical doctrine. It teaches you to keep a critical stance, rather than compulsively following rules imposed by others.

L.M.: And that’s the magic of it, the fact that it makes you think, rather than providing ready-made solutions, isn’t it so?

T.P.: Exactly, exactly. And, eventually, it makes you think not only of yourself, but of others too. Fortunately, we are not alone. The feeling that we are left alone in life is akin to spiritual suicide, after all. Deliberate solitude. The thing is to be capable of overcoming the solitude society creates.

L.M.: Doesn’t writing help with this?

T.P.: Writing helps indeed, but not as much as communicating the written text to others. And if there is something that’s necessary, especially in poetry, it is more public readings. Not individual, not just private readings. Private reading is useful too, it is valuable too, but it is not enough. We shouldn’t forget that, in the past, people used to gather in order to listen to poetry. And there are many such incidents that have had a lasting impact on me. One of them… I think it was around 1984, a world festival of poetry in Morocco, in the beautiful city of Marrakesh, with an enormous square. And every part of the world where there’s a very large square likes to boast that it’s the largest in the world. So in Mexico I was told their square was the largest in the world, and they told me the same in Marrakesh. In other places too. But this particular square was filled with thousands of people, 15 or 20 thousand every night, as they told me, that came to listen to poetry recited in the poet’s own language. There were poets from every corner of the world, and their poems were subsequently translated into French, a language fairly widespread in Morocco. Of course, a few Moroccan poets read their poems in Arabic. But the essence of it was that thousands of people came to listen to poetry.

L.M.: This is truly breathtaking.

T.P.: I was astonished.

L.M.: You surely know that, in Greece too, many young people write poetry, and there are many poetry meetings at small coffee shops and bookstores.

T.P.: I know, and I pray this becomes more widespread. And there is something else. It’s not just recitals before large audiences, but also conversation between poets and writers and those interested in poetry. There is a lack of it in recent years, maybe the spread of the Internet helps isolate people. I believe that conversation is essential both to those who write and those interested in art. Direct, live conversation.

L.M.: You are right. However, I would like to tell you something I’m not sure you are aware of, about how many people read poetry today, and in what ways. I will talk about America, because there is official data available. In 2017, 12% of Americans read poetry at least once a year, a percentage 75% higher than that of 2012. Additionally, about 28% read poetry from printed books, while the remaining 72% use electronic media (e-books, audio, radio streaming). This means that, in our time, 70% of all poetry is transmitted through the Internet. I imagine the same must be true of other developed countries and Europe.

T.P.: What you are telling me is certainly pleasant, but in my opinion - an opinion others also share - poetry is an art that is more often written than read. There are millions of poems written, but people don’t read so much poetry.

L.M.: I think you are absolutely right in this.

T.P.: Yes. And there are many who used to write at some point in life, and never picked it up again. I remember when I was very young, still a teenager, there were many of us who talked about poetry. I don’t see anything like that now. But then, maybe I am not familiar with the way young people behave.

L.M.: In recent years, due to Radio Art, I have been closely watching new poets, and I can see there is a certain movement, initiated by universities, publishers, various associations and clubs, poets are meeting, talking, publishing books. I cannot tell the extent of this endeavor, but it is certainly happening. You were absolutely right in what you said before. There are many who write. You would be amazed if you saw what’s happening in online blogs, how many people are writing poetry. Few read them, as you say. But there are many who write, and this is good.

T.P.: And one more thing, we here in Greece are way behind in this. In organizing poetry events. I have traveled, as a guest, to events in many countries, and I have noticed with interest that there are a great many poetry festivals organized, and many people attending. I already told you about Morocco. There was another time, in Barcelona, at a poetry festival held in a building like our own Concert Hall, with a high attendance. Not only did people have to pay a ticket to enter, but there were many who sold tickets in the black market, and people who bought them. I was frankly astonished.

L.M.: Something like this has never happened in Greece. At least I haven’t heard of anything like it.

T.P.: No, it doesn’t happen in poetry events, even though we like to boast of our great poets, of international acclaim, like Kavafis, Elytis, Seferis, Ritsos and so many others. And yet we don’t organize many poetry events.

L.M.: Did you try to organize something in your younger years?

T.P.: I did, but the effort wasn’t fruitful. There are a few small festivals, mostly in the provinces. There were festivals in Tinos and Syros, for example.

L.M.: I know you recently visited the poetry festival held in Patras.

T.P.: Indeed, Patras held a great international festival last October. Very well-organized. There were both male and female poets from many places. Many came to attend. It was a highly successful event, an initiative of the poet Antonis Skiathas, who lives in Patras and is very active in the field.

L.M.: Yes, I have heard of Skiathas, he is a very notable poet. On Radio Art, aside from poetry, we also place great emphasis on music. I know you too are an appreciator of music, how do you view the relationship between poetry and music?

T.P.: It’s a mutually beneficial relationship, though many times music proves more powerful. Music often absorbs poetry. When we listen to poetry set to music, we mostly retain the music, not the verses.

L.M.: Yes, this is true. I’d like to mention a Greek composer whom I imagine you know, Giannis Christou.

T.P.: Ah, I think he was a brilliant composer and it’s a pity he has been somewhat forgotten, unfortunately he died young in a car crash. I believe that, after Skalkotas, he is the most important Greek composer.

L.M.: Tell us about your relationship with music.

T.P.: I had a great relationship with music from a very young age. Firstly, I listened to a lot of music because my parents were actors in the musical theater, and so I listened to the revues, the operettas, the music of Attik. My father was also friends with Sakellaridis. Afterwards, when I went to the Anargyreios and Korgialeneios boarding school at Spetses…

L.M.: Did you study for many years there?

T.P.: No, I studied until the second year of the eight-class and half of the third year, then schools were closed due to the war. But there was a music club in Anargyreios, where you could listen to a lot of music, and so I began to learn the piano, started taking piano lessons. There was also a philology club, where I could read or listen to music in between classes.

L.M.: What kind of music used to fascinate you, and which continues to fascinate you?

T.P.: At the time I liked Alexander Borodin’s Polovtsian Dances from the opera Prince Igor. And later on, when I returned to Athens after the war, I took piano lessons with my aunt, who was a musician and owned a piano. We didn’t have a piano at home and, when I was 13 or 14, while going to my aunt’s for the piano lesson, I kept thinking, what do I want to be, a musician or a poet? For I couldn’t be both. I had to entirely commit to one or the other. And I decided I would devote myself to poetry. And I got to my aunt’s house and told her, “aunt, I quit the lessons. I won’t come to the lesson again”. She was really sad to hear it, but…

L.M.: This is how it is, after all, life is a “procedure of choices”, is it not?

T.P.: It is, but on the other hand I kept listening to music systematically. I always went to state orchestra concerts. An unforgettable experience. Right after the war, a friend of mine had been sent a portable radio from America, and I asked to borrow it. At the time, it was allowed to enter the Parthenon on the full moon. And I remember one particular full moon, the summer of ‘46, I had just finished school at Varvakeios, and I listened to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony on this portable radio inside the Parthenon. Unforgettable. I later made musician friends like the violinist Tatsis Apostolidis, and they took me to state orchestra rehearsals. And so I came to love Beethoven, not just his ninth symphony but also the seventh, his fourth piano concerto, Mozart’s 21st piano concerto, Schumann’s piano concerto. Brahms’s only symphony. At some point I discovered Beethoven’s last quartets, and I was greatly impressed. Another work I like is Mozart’s clarinet concerto, I often listen to it. But I don’t listen to music as much as I used to, because I cannot stand having good music as a background while doing something else. I have to focus on the music alone.

L.M.: Aside from classical music, did you also listen to Greek music, Hadjidakis, Theodorakis…

T.P.: Yes, I listened to Hadjdakis, Theodorakis and many others. Their contribution is priceless.

L.M.: You belong to those poets who had to work for a living. This wasn’t the case with every poet, however.

T.P.: Let me tell you this. I believe that our modern poetry stems from two great poets who followed two different ways. One was Solomos, the other Kalvos. And the two different ways that began with them were, first, poets who didn’t have to work in order to survive and, second, those that did have to work to earn their daily bread, like Kalvos. I believe this is still true in our time. Palamas became a civil servant, he had a job, and the time he got off work he devoted to poetry. Sikelianos didn’t need to work a single day of his life. Seferis came from a wealthy family, although they fell on hard times after the destruction of Smyrna. Of course, he had a good job at the Ministry of the Exterior, but he still needed to work. Elytis never needed to work.

L.M.: If we take these two major directions, I don’t know if there is a better way to put it…

T.P.: Let us say two parallel ways.

L.M.: Two parallel ways, right. So, concerning the poets who need to work, including yourself, wouldn’t it make sense that their poetry would be more experiential, maybe more sensitive? I don’t know. Do you agree, or do you believe working experience doesn’t affect the poetic result?

T.P.: It can play a very substantial part, since it offers experiences that cause problems and activate both the mind and the soul. But it can also stifle you. It can deny you the time for writing work, which is also essential.

L.M.: But what about writing without working experience?

T.P.: Yes, there is the danger of false experiences, of imaginary experiences unrelated to the essence of life.

L.M.: What is, in your opinion, your distinguishing quality when compared to other poets, what made you stand out so vividly? It is of course hard to judge yourself, but could you give it a try?

T.P.: I don’t want to compare myself to other poets, especially not from a supposedly superior position. No. That’s why, as I have written in the past, the point is not being the best. The point is being different, saying something that you have observed. Expressing one particular aspect out of the many aspects of life that no-one else has ever expressed.

L.M.: I asked exactly in terms of difference. What do you think is different about your contribution to Greek poetry?

T.P.: That is not for me to say. It is hard for me to tell. What I can tell is that I’ve tried to express experiences that were often lost, and to see sides of life that were often dark, either because we didn’t see them, or because the various powers prevented us from seeing them, or from expressing them, when we did see them. My own problem consists in being aware of collective and individual experiences, and overcoming every overt or covert prohibitions.

L.M.: You mentioned the word power, which takes me to another topic. Why do people become corrupt when they reach the upper echelons of power? A historian had said that power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. What happens up there, causing someone who started out with good intentions to abandon them in the process?

T.P.: Power is too sweet, and many who taste it are unwilling to relinquish its sweetness. While the aim of democracy is to keep power in check, bestow no-one with permanent power.

L.M.: Correct, where there’s permanence, as we’ve witnessed all these years, people lose control and are led to situations that are unacceptable, to use an extremely light expression.

T.P.: Yes, and whoever is given permanent power gradually transforms into a covert dictator. And then becomes an overt dictator.

L.M.: I know you are not fond of giving advice, but could you tell me the secret to enjoying life in the face of hardship? For I know you have been through plenty of hardship.

T.P.: It is hard indeed, because it is often the case that the old offer advice to the young in order to justify themselves. Even so, what I think you need to do is resist pressure. You need to keep a critical stance towards events and power, withstand the pressures, but also avoid the temptation to overthrow power and impose your own will.

L.M.: That’s right, we have often seen it repeated in history.

T.P.: Exactly. The problem is keeping power under control, rather than it being a commodity that can be grabbed and retained. This is the toughest part.

L.M.: Democracy achieves this with elections, and the rotation of governments.

T.P.: This is why I believe the frequent subdivision which is often termed geographical, into West and East, is not actually geographical. It separates countries that have democracy at last from those that don’t, that are governed by overt or covert autocracies. And it is fortunate that, today, no country in Europe is under a dictatorship. There are a few countries whose democracy is more restrained, of course, but it is still democracy.

L.M.: This is Europe’s achievement, is it not?

T.P.: Yes, yes. And it wasn’t easy. It required tremendous struggle and sacrifice.

L.M.: You have stated that, in order to instill even a little fear into power, writing must first scare the writer. I imagine you have been scared many times.

T.P.: Yes, I have been scared, realizing what I write might have very unfortunate consequences for me. And there is another thing. When you see things, discover things, and criticize issues you have been a part of and for which you have - at least I did, for a long time in my life - great respect. So you are reluctant to broach them. But your mission carries on, your critique continues, and at some point you’ll have to overcome the restraints and express it.

L.M.: I think you did overcome them, didn’t you?

T.P.: It wasn’t easy.

L.M.: I understand. What was the hardest period you have gone through, and how were you able to overcome these restraints?

T.P.: I gradually overcame them during the time when me and a group of friends published and edited the journal “Art inspection”, when we were obliged to constantly struggle against the doctrines and limitations imposed by the left-wing government of the time.

L.M.: If I remember correctly, “Art inspection” was in circulation for about 12 years?

T.P.: Yes. It began in ‘54 and was shut down by the military junta. Of course I went to Paris in ‘59, I was able to go to Paris, but kept in contact.

L.M.: I know, you provided aid from there.

T.P.: Yes, and I went through all stages of amazement, which were later mitigated or modified. One thing that amazed me greatly in Paris was the Brecht plays I watched. Later in life I cultivated a more critical attitude towards theater, but I still deeply appreciate Brecht’s poetry.

L.M.: How did you react to the great disenchantment of the ideal society that never came? Judging from your poetry, it seems you gradually distanced yourself. How did you get over this?

T.P.: It wasn’t easy, because when ideology becomes blind faith it is hard to leave behind without great external and internal struggle.

L.M.: Were there specific circumstances that made you detach yourself sooner? People that influenced you? Or sociopolitical events?

T.P.: There were many. Mostly experiences at the exiles’ camp of Ai Stratis. Then there were experiences from the then left wing. Experiences after the death of Stalin and the criticism of Stalinism. I believed that the Soviet Union of the time could find its way. That is, the way of democratic socialism, not of autocracy and dictatorship. But I was again proven wrong, and the collapse of the Soviet Union truly shocked me, because I thought it capable of amending all of its shortcomings, and it wasn’t. And I sometimes get the feeling that the tsarist and autocratic traditions still persist. That’s why I’m now such a fervent supporter of democracy, and of moderation, as Aristotle would say, of avoiding extremes. Extremities end up destroying the total.

L.M.: What is, in your opinion, the ultimate catalyst of events?

T.P.: Ideologies turning to fixations, this is the catalyst, and the important thing is not just being morally upright and upstanding, but to view things critically.

L.M.: Could every side maintain a critical stance, or do you think it is difficult?

T.P.: It is difficult, yes, because at the end of the day economic interests are too powerful. And the problem is harnessing these interests, too, placing them under control.

L.M.: This is very difficult, Mr. Patrikios. Going back in time, were there any things that you would have perhaps chosen not to do, or times when you gave in to something only to regret it later?

T.P.: There are three or four things in my life that I would prefer not to have done, concerning friends and…

L.M.: In personal matters?

T.P.: Yes, yes.

L.M.: On a bigger scale?

T.P.: Not on a bigger scale. But as far as everyday matters are concerned, I could tell you one. My father was a wonderful man and I loved him very much, but he had the gambling problem inherent to many actors of his generation. When he was 60, 60 something, he was diagnosed with lung cancer, a result of smoking, because he had been a smoker since childhood. We did everything we could, and finally the doctors told us that the end was near, it was a matter of days. And, my family being under persecution in the aftermath of the civil war, we were terribly impoverished and we had but a little money for the funeral. And one day my father took the money and gambled it all away at the races. And, for the first and only time in my life, I chastised him and spoke harshly to him, and I told him: dad, you shouldn’t have done this, it was outrageous. I have regretted this, and it has tormented me my whole life. That I spoke this way to my father, just before he died.

L.M.: Yes, but we are only human, we are not perfect. It is really moving.

T.P.: I have written a poem on the matter.

L.M.: Which one is it? Do you remember?

T.P.: Forgiveness

Since it’s too late

to ask my father

to forgive me

for matters only known to me,

maybe I should seek forgiveness

from someone else

but, among my acquaintances,

hard as I try, I cannot find anyone

that could truly forgive me.

Sometimes I think that I should seek

my forgiveness

from a stranger on the street

but then again, I burst out laughing

thinking I’d be merely playing

one of Dostoyevsky’s heroes.

L.M.: A breathtaking poem. Do you forgive easily?

T.P.: This may depend. It may have been harder in the past, or now, I can’t really tell. Aye, I forgive, unless it’s something that has hurt me deeply, in which case… I don’t seek revenge, I am not fond of vengeance, but I take my distance.

L.M.: In your long way so far, are there any moments that have remained etched in your memory and you will never forget?

T.P.: Perhaps the most important moment in my life was the 4th of August, a fateful day since the Metaxas regime. But it was in the evening of August 4, 1970 in Paris, at a friendly house, that I met a girl that would become the great love of my life, and vice versa, we later married and my whole life changed.

L.M.: What was your most emotional poetry-related moment?

T.P.: The dedication written for me by Giannis Ritsos, who I both admired and loved dearly. Our paths diverged later on. This dedication gave me tremendous courage.

L.M.: To continue writing poetry, I presume.

T.P.: Yes. It was when I was preparing to publish my first book, the “Dirt Road” in 1954, I had come to Athens on an exile’s leave, and now I can, for the first time, disclose this dedication in public. It is from the book he had published upon returning from exile. Here, you can see it, in Ritsos’s own handwriting.

L.M.: I’m reading it,

“to my beloved friend Titos Patrikios, whose poetic star is destined to light up our sky. With all my heart, Giannis Ritsos, 27/4/1954”.

T.P.: You can see how much strength and courage that gave me in the printing house, working on my own book.

L.M.: Nearing the end of our conversation, I would like you to tell us, in a few words, what life has taught you so far.

T.P.: It is hard to say. Perhaps to respect others, but also not conform to orders.

L.M.: Could we say this is the essence of it?

T.P.: Perhaps.

L.M.: Perhaps it is something else?

T.P.: To never wrong or exploit others. Not that I have always succeeded in that, but I try.

L.M.: I can understand. It is not always easy, is it?

T.P.: Not at all.

L.M.: How would you like to be remembered in the next generations?

T.P.: As a fine poet. As a poet who can offer something in times of hardship or joy.

L.M.: I have chosen a poem from your latest poetic collection “The Way Again”, which came out in 2020, and I am going to share it with the people who will read our conversation on the Radio Art website.

The way and the life

No matter what we say, no matter what we do

no matter what we review, in silence or out loud

others, and even children

will live those same, timeless ordeals

the same unexpected joys, they’ll try

to carve new ways, having set out

on a way much like our own

and changing, or improving

or even torturing life

the life of many faces, unique life

the life of us and others

---

I chose it because I am very fond of it.

T.P.: You move me.

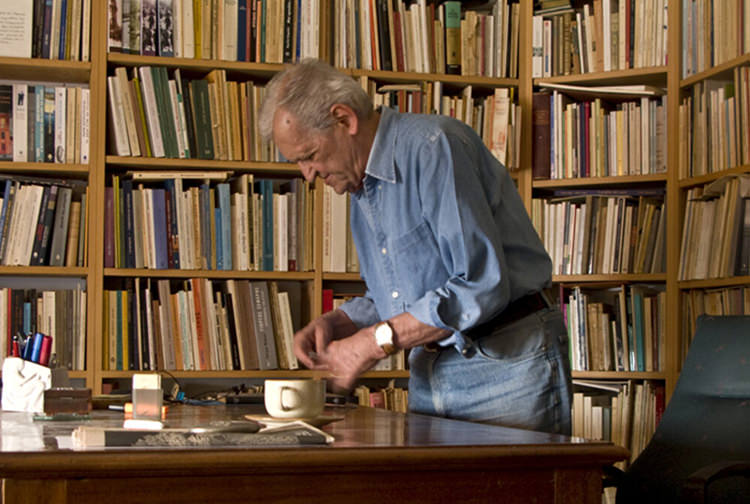

L.M.: I can see around me hundreds of books and texts, even on the floor, I can see an orgy of activity here in your house, I can tell you are in constant search.

T.P.: Indeed, I never cease searching.

L.M.: It was a great pleasure and honor for me and Radio Art to have the opportunity of this remarkable conversation, and I would like to bid you farewell with a couple of my favorite verses by Tasos Leivaditis, I believe he was also one of your own favorite poets, wasn’t he?

T.P.: Yes, and I loved him very much as a person.

L.M.:

So let us write a letter to an imaginary receiver

and let it slip, as if by chance, as we are walking

They’ll find it tomorrow, faded by the rain

then it will have its full meaning.

-------

I believe in fair birds, jumping out of bitter books.

I believe in the unexpected friend you meet in a fairy tale.

I believe in the unbelievable, our truest story.

T.P.: They are wonderful. I would also like to say goodbye with some verses by Leivaditis.

And, o memories, that remember something more than what we lived…

And another one, where he speaks to his dead father:

“..and my father, dead for many years now, comes every night to advise me in my sleep… but father, I say, do you forget? We are the same age now”.

L.M.: Excellent. What a man! One of the greatest Greek poets, in my opinion.

Thank you very much, Mr. Patrikios.

T.P.: I thank you too, our conversation has left me with a very positive aftertaste.

Photo from his award from the Academy of Athens in 2022

Αnthology of poems

Dirt Road (1952-1954)

My boy, you’re nothing like this photograph.

You were a deer, knew every secret lode of water

every woodcutter’s cabin in the glades.

(Tears hanging from the corners of her eyes

like anchors from the fairleads.)

Years of Stone (1953-1954)

The verses, 1

Verses, like children.

They form in your viscera, to secret noises,

suffer inside you, fall ill,

grow unpredictably,

and one day they rise up

against the one who birthed them,

until they leave for good

and are yours no longer.

Attitudes

My attitude

towards life

inspires

my poems.

Once there,

my poems,

shape an attitude

towards life.

Apprenticeship (1956-1959)

The forest and the trees

Verses, 2

……And so I no longer write

to offer paper rifles,

weapons of hollow, rambling words.

I seek to raise but a corner of the truth

shed light on our falsified existence.

As much as I can, as long as I hold!”

Seasonal conflicts

……. “I’ve seen so many kingdoms fall

and others rising in their place

so many high lords brought low

descendants vying for the throne.

Only poetry is eternal.

Don’t waste yourselves in fleeting things.”....

Forgiveness

Since it’s too late

to ask my father

to forgive me

for matters only known to me,

maybe I should seek forgiveness

from someone else

but, among my acquaintances,

hard as I try, I cannot find anyone

that could truly forgive me.

Sometimes I think that I should seek

my forgiveness

from a stranger on the street

but then again, I burst out laughing

thinking I’d be merely playing

one of Dostoyevsky’s heroes.

Optional Stop (1967-1973)

Woman

I

You gave me back my land.

Red soil, light soil

trodden by enemies and tyrants.

You gave me back the gales

of the autumn sea

washing away the dust

from my face

and I felt, beneath my flesh

those same mountain spines

that, through the years

support the homeland.

II

You gave me back my tongue.

Old words, buried

in ruins and ashes

step now into the light

and the day shines

as if the world is made anew

primordial metal of words

thirst, and substantial contact.

III

You gave me back the flow of time

hastening now, or slowing down

the hours

that water my barren fields

without submerging

the statues of me.

IV

You gave me back my city

it lives and changes while I’m away

with all our lost homes

and the covered river.

V

You gave me back the dream.

A strange, trackless sea

a sea of my own

a volcanic island

a gamble with death.

Not knowing if we’ll sink again

or rise from the waters.

Sea of promise (1977)

And the years shall pass

masses of mountain and stone shall block the way

all shall be forgotten

as is the everyday sustenance

that keeps us on our feet.

Everything but that moment

when in the crowded underground train

you held on to my arm.

Paris, May 1960

The resistance of events (2000)

Evergreen Roses

The beauty of the women who changed our lives

deeper than a hundred revolutions

is never gone, the years cannot erase it

even though characters are frayed

even though bodies are deformed.

In the desires they ignited,

the words that led, ever so tardily,

to reckless exploration of the flesh

dramas never made public

reflections of breakups, full identification.

The beauty of women who change life

is in the poems they inspired

evergreen roses, with the same perfume

evergreen roses, as poets always said.

The new line (2007)

The witnesses

My life’s witnesses

are leaving, one by one.

I am now the only witness

to all of my significant

or insignificant moments

and who will believe now

the veracity of my words.

And so I can join

this game of constructs

both for the skeptics and the credulous

change the details to my liking

or, with a stroke of imagination,

simply invent them

yet in the end I give up trying

the testimonies are the same.

Behind my back

sleepless, controlling me

is my younger self.

An age of certainties

In my many years of writing

for a time, I too praised,

though not as loudly as others,

marvelous conquests of mankind

and realities proven false,

powers I took for salvation

as they crushed those close to me

thinking I would be spared --

I too praised love, friendship for all

happiness in equal measure

the new faith

that answered every question.

Looking at so many poems

over two or three generations

they are but shells of an age of certainties

already gone, before the century’s end

The Road Again (2020)

Hope

Pain be fleeting

and love eternal

The way and the life

No matter what we say, no matter what we do

no matter what we review, in silence or out loud

others, and even children

will live those same, timeless ordeals

the same unexpected joys, they’ll try

to carve new ways, having set out

on a way much like our own

and changing, or improving

or even torturing life

the life of many faces, unique life

the life of us and others

Biography

Titos Patrikios was born in Athens in 1928, the son of actors Spyros Patrikios and Lela Patrikiou. He completed his high school studies at Varvakeios in 1946 and entered the University of Athens Law School. He worked as a lawyer for some time. During the German occupation of Greece he became involved with the National Resistance, initially joining EPON before switching to ELAS. In 1944 he was sentenced to death by Greek Axis collaborators and his execution was only called off at the last moment. During his army service he was exiled to Makronisos (1951-1952) and then to Ai Stratis (1952-1953), before returning to Athens on an exile's leave. From 1959 to 1964 he studied sociology at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes in Paris, and took part in research conducted by France’s National Center of Scientific Research. He returned to Greece, but had to flee to Paris once again after the Papadopoulos military coup of 1967. There he participated in events protesting the illegal regime and worked at the Unesco headquarters in Paris and at Fao in Rome. He finally returned to Greece in 1975 and took up work as a lawyer, sociologist and translator of literature. In 1982 he was restored to his pre-1967 position at the National Center of Social Research. He also worked at the Center of Marxist Studies in Athens. His inaugural appearance in the field of letters was in 1943, when a poem of his appeared in the journal “Beginning of Youth”, and his first poetic collection, entitled “Dirt Road”, came out in 1954. As a founding member of the journal “Art Inspection” since 1954, he published many articles and reviews, while several of his essays were included in collective publications. He also took an active interest in translation (texts by Stendhal, Aragon, Mayakovsky, Neruda, Gogol, Garaudy, Lukacs and others) and prose literature. Most of his sociological works were written in French. His works have been translated into French, Flemish, German and Dutch. In 1994 he was honored with a special state award for the entirety of his work. In February 2020, Patrick Maisonnave, the French ambassador to Greece, presented him with the regalia of an Officer of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres.

[Source: Greek Writers Archive, National Book Center of Greece]

Awards:

Special State Literature Award 1994

Academy of Athens, Kostas and Eleni Ourani Foundation Award 2008

Premio Letterario Internazionale "Laudomia Bonanni" 2009

Max Jacob Étranger 2016

Academy of Athens, Kostas and Eleni Ourani Foundation Award 2022